A visit to the British Museum is never a quiet affair. On a recent summer morning, I found myself swept along in the usual tide of school groups, tourists, and Londoners escaping the heat. The grandeur of the Great Court remains awe-inspiring, and the old Reading Room a not to be missed treat, but navigating through it can feel like trying to cross a festival crowd. That same chaotic energy accompanied me into the exhibition space for “Hiroshige: Artist of the Open Road.”

I wasn’t quite prepared for the popularity of this show. The rooms were quite tightly packed, visitors inching along the displays in reverent clusters, craning necks and squinting for glimpses of the quite small delicate prints. It was, paradoxically, a rather noisy immersion into one of the most lyrical, quiet bodies of work in the history of printmaking. Yet once a little further inside— the initial bustle fading—the exhibition offered a beautifully comprehensive journey into Hiroshige’s world, one in which roads wind through misty valleys, and fishermen stand motionless beneath driving rain.

The British Museum has done an admirable job not just in displaying Hiroshige’s woodblock prints, but in contextualising their creation and cultural significance. Videos and didactics along the way detail the complex, highly collaborative process behind each image. This wasn’t merely a solo artistic pursuit: every print involved at least four creative parties—the publisher, the artist, the block carver, and the printer. Watching a block carver painstakingly trace and cut Hiroshige’s fluid lines brought new appreciation to the craftsmanship required, so much so, we were inspired to visit the amazing art supplies of Cornelissnand and Son, just down the road, and look at their vast selection of print carving tools. But back to the exhibition. Explanations of the differences between various editions of prints—some brighter, some more subdued—added more context and helped to illuminate how ukiyo-e prints, though mass-produced, were anything but uniform.

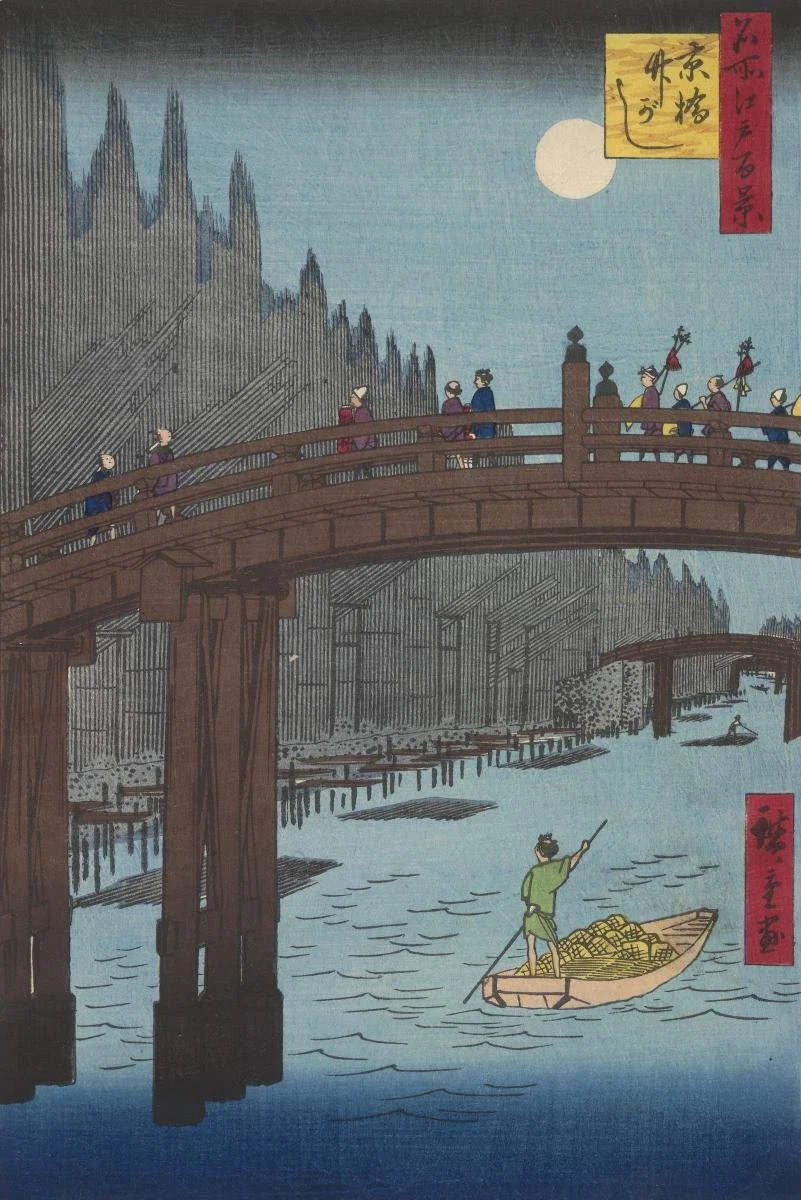

Hiroshige, best known for series like The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō and One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, reveals himself throughout the exhibition not only as a master observer of nature, but as something of a poet in visual form. His ability to render the everyday—travellers crossing a bridge, a sudden rainfall, distant mountains veiled in mist—with such expressive force feels both intimate and universal.

What struck me most, though, was how modern so many of the prints felt. Some landscapes, reduced to bold diagonals of road and sky, verge on abstraction. A bridge becomes a sweeping curve cutting across the page; a boat turns into a dark, minimal silhouette on a silvered sea. There’s a sense of rhythm and design here that feels surprisingly contemporary. It’s as if Hiroshige was not simply documenting the landscape, but re-imagining it—distilling the essence of landscape rather than reproducing the detail of it.

The exhibition gently draws attention to Hiroshige’s influence on later Western artists, particularly the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, and it’s easy to see why. The flattened perspectives, the play of empty space, the unexpected cropping of forms—all of it resonates with the innovations of artists like Van Gogh, Whistler, and Monet, who were featured in the exhibition. But even without this historical footnote, Hiroshige’s work stands tall in its own right: sensitive, inventive, and deeply attuned to the poetry of place.

Despite the crowds and the slightly hectic atmosphere, “Hiroshige: Artist of the Open Road” felt like a moment of stillness in the heart of London. The show does more than showcase beautiful prints—it invites us to reconsider how we see the world: not just as it is, but as it feels. Amid the noise and movement of daily life, Hiroshige offers a quiet, open road, winding through rain and sunlight, always just ahead.